Hemingway’s Paris memoir

I’ve been obsessed with Ernest Hemingway’s works ever since I was a child – the classic dialogues were shown telegraphically while those fascinating details were presented exquisitely. And I can never get bored from the stirring plots that silent forests were lightened up with bullets flashing through, that a riot broke out in the burning sun, and that the enormous marlin lurking in the deep blue water. It seems that Hemingway was always praising the glory and pride of life in his works, in which his unfettered freedom and fair loneliness can never be hidden. And even if this is the fifth time that I’ve opened the book, A Moveable Feast, I’m still amazed by the unique sense of pride and fair loneliness that Hemingway possessed.

The bustling Paris in the 1920s

If most of Hemingway’s works are compared to surging tides in the silent night, then the fabulous book, A Moveable Feast, is more like a lonely blossom in the chilly, early spring, waiting for the vibrant nature. The book is a full-length novel consisting of several short stories and informal essays, storing the priceless memories of the good old days that Hemingway and his wife spent in Paris. Although the novel was born in the smoke of the Cuba Revolutionary War, it is those placid yet thought-provoking stories that the memoir contains – the café on the Place St-Michel, the sunset on the Seine River, horse racing, new friends, and travel. Hemingway showed us the moveable feast, a cultural feast moving in the streets of Paris, using unfettered sentences in which his strong desire for loneliness can be found transparently.

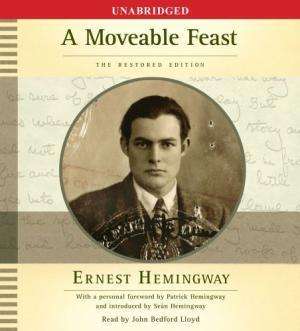

The bookstore has witnessed the feast

Whenever I enjoy the novel, it seems as if Hemingway is wandering in the streets of Paris just in front of me, murmuring his thoughts to a silent statue standing at the center of a cross. The instructions from Miss Stein, the Shakespeare and Company bookstore, and the devil’s disciple, Scott Fitzgerald, Pascin and Ezra, Hemingway hid the fancy cultural feast in ordinary trifles calmly without prejudice, as if he were nothing more than an attentive bystander. And without extra euphuism and modification, the novel seems to be a relaxing road trip in the countryside accompanied with Artur Rubinstein's Nocturne.

Young Hemingway in Paris

What amazes me the most is that Hemingway showed me a kind of “old-fashioned” attitude towards life – that pursuing appropriate loneliness from time to time offers one a stronger ability of thinking independently. A famous professor from Fudan University once said: “Those who pursue fair loneliness possess a harmonious spiritual world.” Living in such an acquisitive society, have we ever desired to run away, enjoying the moments when we are just alone with ourselves, or we just give in and conform? Hemingway was once in that cultural feast where various opinions confronted each other, but he had never given in to the trend, nor had he ever give up expressing himself. Hemingway seems to be pursuing loneliness in the crowd all his life, but he wasn’t lonely for those run-aways are just a chance for him to reflect on himself, get a better view of Paris and enjoy the good time of early spring.

The moveable feast might be the major content of the memoir, however, the deeper I’m immersed in the book, the more I’m impressed by Hemingway’s strong desire for fair loneliness, which will always be a reminder for me that fair loneliness is not only beneficial for completing our personalities, but it’s also respect and response to our true desire, just like Hemingway insisted on his fair loneliness, enjoying the cultural feast with the original aspiration even in difficult times.